When I read news articles about someone who’s taken their life, I always find this inner-voice screaming why? Every suicide I read about appears to be unexpected, and the descriptions of the deceased person always appear to be unaligned with someone in crisis, and separate from some people unwilling or unable to share their pain with others, I think there is another reason suicides are so often unexpected.

99.99% of people any given year in Australia won’t take their life. So perhaps, part of the reason we see suicides as unexpected is because it’s incredibly rare. When we adjust this figure to people attempting suicide, 99.75% of people any given year in Australia won’t attempt suicide. Suicides and attempted suicides are definitely priorities for our society, but one reason they always kick us in the teeth, in addition to their tragic nature, is because of this rarity, so we’re left asking ourselves…how, and why, has this happened?… but we’re too often asking this question after the fact, not before it.

Having lost my Dad to suicide in 2010, it certainly felt like a curve ball at the time. With the benefit of hindsight and particularly through my studies, reading, and this rag, there are narratives that can be constructed to explain why my Dad took his life. But this is almost irresponsible because I can never be certain, I can only believe that some things probably caused his death… finding out WHY someone takes their life is incredibly difficult, and perhaps it’s a question that will be answered down the road… but finding out HOW someone arrives at a mental state to think taking their life is appropriate, at least to me, appears far more achievable. And if we can figure this out, we can help people before they arrive at this point.

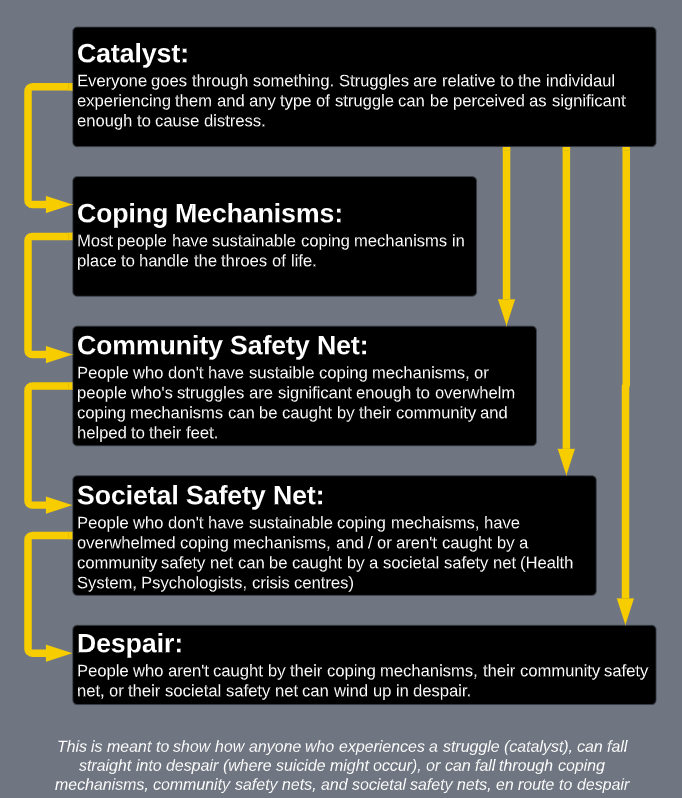

I need to preface by saying that there are exceptions to the below, but I believe that this framework captures most of the journeys toward suicide. I also need to preface that the catalyst is filled with innumerable scenarios, but they all share a common theme; causing pain that is perceived (either consciously or subconsciously) to be significant.

Catalyst

There are certainties in life, and one of those certainties is that at some stage, we’ll feel rubbish. Every struggle and pain is relative to the individual experiencing it and whilst we might be able to objectively rank some struggles, each person can lay claim that one moment in their life was the hardest thing they’ve been through. There’s no skirting this fact… we might be able to use perspective to increase gratitude that our pain isn’t worse, and this can mitigate the pain, but it will always be the worst pain we’ve felt. As mentioned, these pains can be ranked from objectively horrible things to go through, to mounting pressures of responsibility, financial stress, or other ongoing stressors, all the way to diseases of modernity, where because our lives are the best they’ve ever been, ripples can feel like tsunamis. The point is, any struggle can be a catalyst for someone to fall into despair or rely on their coping mechanisms.

Avoiding all catalysts is futile. Avoiding some catalysts is necessary. There are certain hardships that no one should have to endure and there are certain hardships that we or our society can be reasonably expected to solve over time. But ultimately, because struggles are relative to the individual experiencing them, they will always exist. Because of this, we need to prepare for pain, not avoid it.

Coping Mechanism

Our coping mechanisms are key to how well we navigate the throes of life. They are made up of habits we resort to when placed under pressure and they can either lead to growth or harm. Ensuring our coping mechanisms are made up of habits that ultimately lead to more positive outcomes is key… but not everyone has them, and nobody has coping mechanisms that are 100% positive. Coping mechanisms can be things like what we eat when we’re stressed, whether we exercise, whether we isolate ourselves or reach out to friends, whether we drink alcohol, how much we sleep, what activities we resort to… work, social media, chores… The list goes on, but they are our behaviours during tough moments and they are directly relevant to how well we survive through these moments. I read a fantastic book that summarises these coping mechanisms as part of our resilience shield, which is made up of six layers (outlined below)

It’s important to note that even if we have our resilience shield as strong as possible, we can still be overwhelmed by the pressure of life, and may need help from the two safety nets outlined below.

Community Safety Net

Unlike how the community provides meaning and purpose above (social layer of the resilience shield), the community also acts as a safety net. From people checking in with someone after they missed a training session or didn’t turn up to work, all the way to someone reaching out to a community member to help, or be helped, the community safety net acts as a support structure. Furthermore, the community safety net is incredibly powerful because people being caught in the safety net will experience greater purpose within that community, making them more likely to contribute to that community, consequently strengthening the coping mechanisms of all involved.

Societal Safety Net

The people who either don’t have a community or fall through the community safety net can be caught by society’s safety net. These are things like the general health system, psychologists, and crisis centres. These mechanisms are solutions designed to fill gaps identified by the community and the government. They do incredible work and they are necessary for a suicide-free society. Despite their necessity, they are further downriver, and their importance within a long-term lens, in my opinion, is secondary to empowering people to be self-sufficient and strengthening the community safety net.

Despair

If someone experiences a hardship, doesn’t have the appropriate coping mechanisms, and isn’t caught by either the community or societal safety nets, over time they might find themselves in despair. Once in despair, their lifestyle, their thought patterns, and their perspectives will begin a downward spiral towards hopelessness, a feeling of being burdensome, and loneliness, which is where people can justify suicide as a viable option. If you’re in this position right now, I promise you there’s another way, and you can start along that path by contacting someone right now.

At the very least, Lifeline can be called on 13 11 14.

So what does this tell us?

It is impossible to remove struggle altogether because it is relative to all other inputs. Therefore, instead of avoiding pain, it reiterates the importance of preparing for pain, by building sustainable coping mechanisms. It also reiterates the importance of preparing communities to catch people who’s coping mechanisms have failed, in either propping them back up or redirecting them to the appropriate societal safety nets. And lastly, it reiterates the importance of having a large enough societal safety net to catch all those who fall through the cracks. Furthermore, I think it’s imperative that we start looking down the road to prevent problems in the future, and in my opinion, that looks like building individual and community resilience.

Now, this might seem all hunky dory, beer and skittles, and perhaps the way in which we achieve this is more complicated than it appears, but the concept is there in my opinion. If we build resilience in individuals and communities, we are reducing the stress on the societal safety net and increasing our capacity to cover up the cracks people are falling through. Additionally, it’s important to note that as we save more lives, the lives that still need saving are likely to be more nuanced and difficult to save. To use an analogy, it’s akin to shifting a pile of sand, 95% appears straightforward… you just stick the shovel in and move it to the wheelbarrow… It’s hard work, but we know what we’re doing… as we get closer to the bottom of the sand pile though, we start to notice how hard it is to pick up each granule, and if we’re going to pick up every single bit of sand, we start to need things like vacuum cleaners and lint rollers. While saving lives is more difficult at this stage, this difficulty is associated with having saved lives before. It is a derivative of success… whilst it can appear frustrating, it’s ultimately a good problem to have.

I don’t think I’m being cruelly optimistic in my thinking but this is the importance of Open Source Thinking, I need you to challenge these notions, add to them, or share them. We are at the start of this journey towards a suicide-free Canberra and whilst we have more questions than answers, as we progress, that balance will begin to shift.

Again…

As I proofread this… I am fully aware of the exceptions to the rules outlined above… this is not an exhaustive analysis of how someone arrives at a mental state to think taking their life is appropriate. This is an attempt to continue the discussion and bring more heads to the table, so we can find a solution.

You make a really good point about the struggle being relative to the individual experiencing it.

10 people can go through the same hardship or trauma and maybe only 1 or 2 might struggle or be visibly impacted. All too often we dismiss these 1 or 2 as ‘weak’ and the others as ‘strong’, but this fails to take into account all the other variables in a person’s life. What past trauma do they carry, what supports do they have, what tools and strategies have they developed, what other stresses do they have in their life?

The conversation about mental health needs to reflect this without judgement, just acknowledgement and understanding of the impacts.

“Society is focused on avoiding pain, rather than preparing for it” - terrific observation mate. Tough times are inevitable no matter what progress we make on any front re disease, financial equality etc, because the better things get, the bigger the tsunami will feel